A LITTLE OF CRANKO, SOMETHING OF BALANCHINE AND A LOT OF UWE SCHOLZ

PARIS, 14 February 2000 - Prologue: The Legacy of The Stuttgart Ballet

___ In

1960, John Cranko, the far-sighted South African born choreographer,

went to stage his Prince of the Pagodas in Stuttgart and remained there

as ballet director. His repertoire made it one of the most important

companies in Europe, his school ensured its future, and his guidance

and encouragement to the dancers to choreograph produced a wealth of

talent which included John Neumeier, William Forsythe, Jiri Kylian,

(who in turn inspired Nacho Duato), and Uwe Scholz, winner of the Prix

Allemand de la Danse last spring. ___

___ BY PATRICIA BOCCADORO ___

___ French

audiences were privileged to see a programme of Scholz' work at the

Théâtre de Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines recently which demonstrated

his exceptional musicality, his choreographic inventiveness, his respect

of beauty and harmony, and above all, his ability to translate great

music into another art form. ___

A

Conversation With Uwe Scholz, Director of the Leipzig Ballet

___ When I met Scholz, now forty, but who seems barely older than dancers half his age, at the Théâtre de Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines where his company was appearing on their first visit to France, he spoke of the three people who had most influenced his life. Recalling the meeting with Cranko, the man who choreographed such great classics as The Taming of the Shrew, Romeo and Juliet, and Onegin, Scholz told me, "I was only thirteen when I met him in May 1973, the month before he died. I had gone to audition for his school in Stuttgart and knew instinctively that he liked me........the ballet masters were not so sure! There was an immediate complicity between us, although I hadn't seen any of his choreography." ___

___ "Cranko's ballets are full of generosity and human warmth. He doesn't just make use of a score, but makes his ballets come alive through it, whether in long narrative works or in the shorter choreographic jewels like Jeu de Cartes." ___

___ A

five-month stay in New York introduced the eighteen-year-old student

to George Balanchine whose ballets he found more detached, but superbly

conceived. He was fascinated by their luminosity and extraordinarily

clear structure. ___

___ "It

seemed as if he was working with a very sharp knife ," Scholz said.

"He knew exactly when and where to cut, and everything he created

is marked by an incredible musicality. The greatest compliment anyone

can pay me is to compare my work to his and Cranko's, for they are the

undisputed masters of the twentieth century. I would happily like to

be considered as something of Cranko, plus a little of Balanchine, shaken

up well and spat out a quarter of a century later!" ___

___ Logically,

Uwe Scholz' early musical education at the Darmstadt Conservatory, where

he studied the piano, the violin, the guitar and singing, as well as

dance, should have led him to fulfil a childhood ambition to be a conductor,

but at seventeen he realised with surprise that he had become a choreographer.

___

___ It

was John Cranko's muse, the Brazilian ballerina Marcia Haydée,

who, inviting the shy adolescent to choreograph works for the company

shortly after she became the artistic director of Stuttgart, determined

the course of his life. In 1980, two years after writing his first work,

Serenade pour 5 + 1, music Mozart, he abandoned dance, to become the

troupe's first resident choreographer since Cranko's death. ___

___ Since

then, Scholz has created over a hundred ballets not only for his own

company and Stuttgart, but for other troupes including the Ballet of

Zurich, which he directed for six years, the Nederlands Dans Theater,

La Scala-Milan, Vienna State Opera Ballet and Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo.

___

___ It was in 1991 that he was invited to take over the Leipzig Ballet, the largest city in East Germany after Berlin. The troupe had known a glorious past in the aftermath of the romantic era, but had been reduced to a motley collection of tired, disheartened dancers after the collapse of the Berlin Wall and withdrawal of state funding. It is no secret to anyone that despite possessing possibly the greatest classical choreographers working in the world today, Germany still gives priority to the orchestras. ___

___ "The

history of Leipzig, Wagner's birthplace, is magical", Scholz told

me. "Many parts of the old city, including the Jewish quarter,

have been restored, and you are surrounded by the atmosphere of the

past, by the ghosts of Schumann and Mendelssohn. I'm old-fashioned and

love to choose romantic classical music, and although I suspect there

are those who regard me as the last of the dinosaurs, I never mix styles,

preferring to use whole scores. In Classique. Symphonique (music Prokofiev,

Rachmaninov; decor Scholz after Kandinsky), the basic ideas were inspired

by the composers and the painter themselves. The three of them meet

and, I hope understand each other in my work." "Moreover,

I'm fairly traditional with a neo-classical style. I work mainly on

pointe, using classical steps and my aim is to transmit an emotion.

I have fifty dancers of twenty-two different nationalities, which is

both an advantage and disadvantage. I have to give them all one style

as only two or three were trained at my own school; I'd like to hire

more, but there is no money available". ___

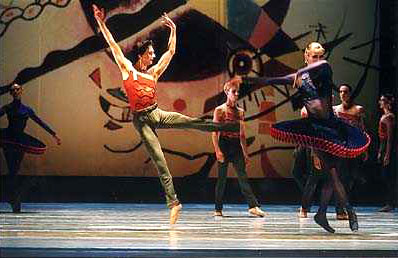

Classique Symphonique.

Photo: Andreas Birkigt, Oper Leipzig

___ "I've been under criticism for only presenting my own work, but this was through financial necessity. With the prize money I won recently, we staged John Cranko's Onegin in June, and are able to invite Robert North and Jiri Kylian next season. Indeed, the last thing I want is a company of one choreographer; it's important for my dancers to have the experience of working with others, for it will also affect their interpretation of my ballets." ___

___ While Scholz has created several ballets to shorter pieces by Mozart, many, like his 1985 masterpiece, La Creation (oratorio in three parts, by Joseph Haydn), also programmed at Saint-Quentin, rely on complete scores by Schumann, Bach, Beethoven, Berlioz, or Prokofiev. ___

___ They

are never abstract works, but are written to see below the surface of

the music and discover more about the composer himself. "Right

now," said the choreographer, "I'm working on Bruckner's Eighth

Symphony, to be premiered in Leipzig on December 17th, so I'm coloured

by his life. I live, think, and breathe his music." ___

___ As

does his choreography. However, the composer to whom Uwe Scholz refers

to repeatedly in conversation was not born in the nineteenth century

but is very much part of the world's cultural life today. He has immense

admiration for Pierre Boulez, who has fortunately given Scholz permission

to use his work, although he has not written music specifically for

him. ___

___ Scholz'

ballets are a bridge between past and future. His genius and sensitivity

ensure that classical dance remains very much alive, and his ballets

as well as those of John Cranko and Kenneth MacMillan before him will

continue to be danced by future generations. They are not merely products

of inflated egos like so much of the experimental and gimmicky pieces

flooding France today. ___

http://www.culturekiosque.com/dance/inter/rheleip.html